![[Tudor standard]](../images/g/gb-tudst.gif)

image by Rob Raeside

Last modified: 2015-02-21 by rob raeside

Keywords: united kingdom | tudor | naval ensign | baffin arctic expedition | pennants | streamers |

Links: FOTW homepage |

search |

disclaimer and copyright |

write us |

mirrors

The House of Tudor was a English royal dynasty that lasted 118 years and ruled between 1485 to 1603. The Tudors emerged from the Wars of the Roses as England's new rulers. The first Tudor to rule England was Henry VII (1485-1509). Born Henry Tudor, he married Elizabeth of York of the House of Plantagenet thus uniting the two families. He was followed on the throne by his son, the powerful Henry VIII (1509-1547), then Edward VI (1547-1553), Mary I (1553-1558), and finally the legendary Queen Elizabeth I (1558-1603). The Tudors transformed the English navy into the most powerful naval force of its day.

English naval ensigns did not begin to be standardized until shortly before the Civil War. Therefore, Tudor ensigns varied from ship to ship. In 1896, flag historian Fredrick Hulme commented that "A hundred years ago or so, we may see that there was a considerable variety in the flags borne by our men-o'-war. Such galleries as those at Hampton Court or Greenwich afford many examples of this in the pictures there displayed..." Each of these were hand made and thus tended to be made in different materials and styles with no two exactly alike. They usually had horizontal stripes, in various colors, some with a canton and some without a canton, some with an overall Saint George's Cross and some with the Saint George's Cross in the canton.

Pete Loeser, 4 October 2012

The presentation mainly concerned flags used at sea by Henry VIII's navy. Such flags served three purposes - decoration, identification, and information transfer. Decorative flags were used to glorify the prince, and were not used during rough weather or in battle. In order to understand the use of flags in battle in the early 16th Century, it must be noted that the concept of the sea battle was still being developed. Before the invention of guns on board, galleys fought mainly by ramming each other. With the appearance of guns in the early 15th Century, galleys began to fight as individual ships, although such battling was rare outside coastal waters or more sheltered seas like the Mediterranean. Sailing ships in use up to the late 16th Century were clumsy, and major sea battles were more by accident than by design. Sea battles were essentially land-type battles, fought at sea. Ships therefore copied land-based forces, and carried the arms of the travelers.

To demonstrate the decoration used by Henry VIII's ships, consider the record of purchase of flags for Grace à Dieu, his new flagship, in 1514. It was decorated with a 51 yard green and white streamer, 3 20 yard streamers, 3 5.5-yard long streamers, 10 3-yard long streamers, 10 St. George cross flags, and the image of the lion, the dragon and the greyhound (all provided at a cost of £112 19/8d). (See image above for an idea of the appearance of the streamer.) Some flags at this time were mostly streamers or banners, and some were made in metal. Special flags were made in fine wool or silk and embroidered.

At this time, ships were made or commandeered as needed for battle. After the battle, most ships reverted to the previous tasks. After the French War of 1512-14, Henry retained a fleet of 15 ships, essentially the beginning of the English navy. By 1545, the Naval Council existed with about 60 ships. Even in a smaller fleet, it was necessary to denote which ship carried the admiral, and this was accomplished by flying the St. George Cross flag from the mizzen mast. With the introduction of a larger fleet, flags became used as signals of the squadron to which the ship belonged, initially by flying a flag on either the foremast, the top mast, or the mizzen mast. Arms were used abundantly to identify who was on board.

Henry VIII died in 1547, and [according to David Loades], by 1588, only the royal arms, the national flags, and the squadron ensigns (by this time red, blue and white flags, for the first, second and third squadrons respectively) were used. [disputed]

Rob Raeside, 8 August 2001

[Editorial Comment: This ensign is a "typical" example of the naval ensigns used during the Tudor Period, although the ratio shown here is based on more modern replicas. Some other examples follow using ratios more commonly associated with the Tudor period.]

A fleet of four English squadrons and one Dutch squadron were sent to Cadiz in 1596. Lord High Admiral, Howard of Effingham, was Joint Admiral of the Fleet, and led one squadron. Robert, Earl of Essex, was the other Joint Admiral, and led the second squadron. Lord Thomas Howard, Vice-Admiral, led the third squadron. Sir Walter Raleigh, Rear-Admiral, led the fourth squadron. Each squadron then had its own Vice-Admiral and Rear-Admiral.

Two flags (shown by Perrin, 1922) were flown by the following admirals:

St George canton and striped field:

Blue barred St George:

![[possible Elizabethan ensign]](../images/g/gb~tva.gif) image

by Martin Grieve

image

by Martin Grieve

![[possible Elizabethan ensign]](../images/g/gb~tva2.gif) image

by Christopher Southworth

image

by Christopher Southworth

From Sir William Slyngsby's "Relation of my Lord of Essex voyage to Cales",

a manuscript in the Duke of Northumberland's collection reproduced in

Navy Records Society's Naval Miscellany volume 1; edited by Sir Julian Corbett,

1902.

David Prothero, 6 May 2004

The stripes in question are a greenish-blue. However the intended colour must be blue as exactly the same colour is used in the fleur-de-lis quarters of the royal standard. Perrin's account of the flags used on the expedition differs from the Naval Miscellany that he is quoting, in two respects. The last sentence of the penultimate paragraph on page 88 of "British Flags" reads; "The Vice- and Rear-Admirals of his squadron flew at the fore the St George barred with blue horizontally." I think that the words "and mizzen respectively" have been omitted after the word "fore". In middle of the same paragraph, the flags of the Vice- and Rear-Admirals of the Lord High Admiral's squadron are described as:

"..., a flag with striped field (red white and blue in seven horizontal stripes) and the St George in the canton." The stripe which is described as "red" is not the same colour as the cross of St George in the canton. It is brown. Perhaps the heraldic stain tawny ?

The Editor of the Naval Miscellany, Sir Julian Corbett wrote, "The tinctures of

the squadronal flags of 1596 as here represented are difficult to account for. The green and white are of course the ordinary Tudor colours. But the tincture of the first two squadrons bear no relation, as might have been expected, to

those of the arms of Essex or Howard, or to those of any of the Queen's standards."

To summarise the admiral's flags used in the 1596 Cadiz expedition. The four English squadrons had the usual three ranks of admiral, vice-admiral and rear-admiral, but the full admiral of each squadron was also a fleet admiral; two were Joint Fleet Admirals, one was a Fleet Vice-Admiral and one was a Fleet Rear-Admiral.

The Discovery Channel carried a documentary account of the life and adventures of Sir Francis Drake. It showed

his vessel The Golden Hind sailing up the west coast of South America and capturing several Spanish treasure ships off the coast of Peru. The flag flown on the Golden Hind consisted of four broad green vertical stripes separated by three broad white ones. In the canton was what looked like an English flag, but the arms of the St George's Cross were much broader than one commonly seas. Is there any info regarding this flag?

Ron Lahav, 26 December 2004

I have never come across an ensign of the period with vertical stripes (although references are scant) but it would appear that the actual design was very much a matter of personal choice? Green and white were, of course, the Tudor livery colours and very popular in flags up to the Stuart accession, and what information we have suggests that the canton of St George was (with the odd exception) almost universal until 1707. The width of the arms of the St George

varied considerably, so no significance need be attached to their size. As a matter of personal opinion only, I would have been inclined to have made the stripes horizontal, but given the 16th Century's freedom of design there is no

real reason why such a flag should not be used? Indeed, I would not be at all surprised if someone came up with an exact reference.

Christopher Southworth, 27 December 2004

In earlier times, a stern ensign was apparently something of a a luxury - a special occasion flag - with what evidence we have listing only one per ship (together with an ensign staff to fly it from), and there was certainly no

regulation or convention extant with regard to the colour, number or disposition of the stripes. As examples, one source I have gives the naval ensign of c1623 as having 15 horizontal stripes alternately blue, white and yellow with a Cross of St George in the canton, whereas the flag of the Honorable East India Company (which may or may not date from the end of Queen Elizabeth's reign) is often shown with thirteen - we have visual evidence that the striped ensign was in use by HIEC ships in the 1660's, but no way of knowing whether the ensign ("auncient")

listed in an inventory of 1601 was of this type?

Christopher Southworth, 22 May 2006

The use of multiple ensigns and flags flown from the masts to ceremonially decorate Tudor ships seems to have been the general practice of the times, and is sometimes confusing especially with the apparently interchangeable terms used to sometimes describe them. We have chosen to use the term "pennant" for the shorter ones and "streamer" for the longer ones here, some which appear to have reached prodigious lengths at times.

According to Frederick Hulme: "The Pennant, or pendant, is a long narrow flag with pointed end, and derives its name from the Latin word signifying to hang. ...some of the flags employed in ship-signalling are also of pennant form. It was in Tudor times called the streamer. Though such a flag may at times be found pressed into the service of city pageantry, it is more especially adapted for use at sea, since the lofty mast, the open space far removed from telegraph-wires, chimney-pots, and such-like hindrances to its free course, and the crisp sea-breeze to boldly extend it to its full length, are all essential to its due display. When we once begin to extend in length, it is evident that almost anything is possible: the pendant of a modern man-of-war is some twenty yards long, while its breadth is barely six inches, and it is evident that such a flag as that would scarcely get a fair chance in the general "survival of the fittest" in Cheapside. It is charged at the head with the Cross of St. George."

Source: The Flags of the World (1896) by Frederick Edward Hulme, p 20

Pete Loeser, 5 May 2012

image by Tomislav Todorović, 02 May 2013

In the description of one of the City pageants in honour of Henry VII. we find among the "baggs" (badges), "a rede rose and a wyght in his mydell, golde floures de luces, and portcullis also in golde," the 'wallys' of the Pavilion whereon these were displayed being 'chekkyrs of whyte and grene.'"

Source: The Flags of the World (1896) by Frederick Edward Hulme, p 26

Image Source: Plate Three

image by Tomislav Todorović, 02 May 2013, based on Wikipedia image of badge of the Portcullis Pursuivant of Arms

Image Source: Plate Three

image by Tomislav Todorović, 02 May 2013, based on Wikipedia image of the Tudor Rose

Image Source: Plate Three

image by Tomislav Todorović, 02 May 2013, based on Wikipedia image of the flag of Wales

Image Source: Plate Three

The Tudor naval streamer was a long, tapering flag, flown from the top of the forecastle, between 20 yards or longer in lenght, and up to 8 yards wide. For example, according to period records, the ship that took Beauchamp, the Earl of Warwick, to France in the reign of Henry VII flew a "great streamer" 40 yards in length and 8 yards wide. About the closest thing to a Tudor streamer today would be a Royal Navy commissioning pennant, which, in addition to the white ensign, is flown as a long streamer from the maintop gallant masthead.

Pete Loeser, 5 May 2013

A streamer shall stand in the toppe of a shippe, or in the forecastle, and therein be putt no armes, but a man's conceit or device, and may be of the lengthe of twenty, forty, or sixty yards." — Harleian MS., No. 2,358, dealing with "the Syze of Banners, Standardes, Pennons, Guydhomes, Pencels, and Streamers."

Source: The Flags of the World (1896) by Frederick Edward Hulme, p 26

Image Source: Plate Three

image by Tomislav Todorović, 02 May 2013

Image Source: Plate Three

image by Tomislav Todorović, 02 May 2013

Image Source: Plate Three

image by Tomislav Todorović, 02 May 2013

image by Tomislav Todorović, 02 May 2013

image by Tomislav Todorović, 07 May 2013

image by Tomislav Todorović, 07 May 2013

Source: Chapter Two

Image Source: Plate Eight

image by Tomislav Todorović, 07 May 2013

image by Tomislav Todorović, 07 May 2013

Source: Chapter Two

image by Tomislav Todorović, 07 May 2013

image by Tomislav Todorović, 07 May 2013

The flags with same design were hoisted at three mastheads of the ship.

Source: Chapter Two

Image Source: Plate

Seven

image by Klaus-Michael Schneider, 8 May 2013

image by Klaus-Michael Schneider, 8 May 2013

An 11-stripes flag divided horizontally into alternating green and white stripes, according to source flown in the 16th Century.

Source: E.H.H. Archibald: Dictionary of Sea Painters, flag chart opp. to p.20, flag no. 25.

Klaus-Michael Schneider, 8 May 2013

In 1603 the House of Stuart replaced the House of Tudor as England´s ruling family with Elizabeth's death. James VI of Scotland became James I of England. Around 1620 we began to see the striped Tudor ensign give way to naval ensigns with solid-color fields. By the middle of the 17th Century the three basic British flags had become the Cross of St. George, the Union Flag, and the Red Ensign with a canton of the Cross of St. George.

Pete Loeser, 5 May 2013

Ensigns using a striped format are known to have been flown by the Navy Royale until the late 1620's, and some parts of the merchant service somewhat longer - it is known, for example, that the red and white striped ensign of the Honourable East India Company was still in general use by ships of that company in 1673.

Christopher Southworth, 6 May 2013

See also: Possible sightings of striped ensigns after 1630

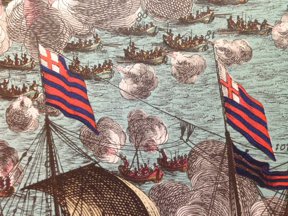

Image from Pete Loeser, 27 July 2014

Image from Pete Loeser, 27 July 2014

This flag is illustrated in a painting of the siege of La Rochelle. It was submitted to FOTW for identification.

The siege was about Louis XIII breaking the edict of Nantes and then having

to defeat the Huguenot uprising he caused, which he did despite some English

efforts to lift the siege. The interesting bit is that I only know these as

mono-colours. But if this is like the original and if the contributor has the

whole thing, then the identifying numbers can be looked up in the index below

it.

Peter Hans van den Muijzenberg, 12 August 2014

The contributor agreed that this is the "Siège de La Rochelle", and also that all other images are colourless. His has been framed without the index, and he has no way to determine whether the colour is genuine or added later. Nevertheless, he thanks us for adding that bit of information.

Next step would be to find such a colourless image that has the same print, where we can make out the numbers with certainty, and then find an index to look them up in. Anyone any ideas? But, with nothing definite on this print these colours might, of course, still be a colourer's fancy.

Peter Hans van den Muijzenberg, 23 August 2014

enlarged detail by Rob Raeside, 19 July 2014

enlarged detail by Rob Raeside, 19 July 2014

Historically, at La Rochelle the royal forces of Louis XIII placed the French Protestant Huguenots under siege, and the English fleet sent by the English King Charles I attempted to lift the siege. The tensions between the Catholic French and the Protestant Huguenots climaxed at La Rochelle and ended in complete victory for King Louis XIII and the Catholics. This striped "Tudor style" English naval ensign can be clearly seen in this detail illustration.

Pete Loeser, 27 July 2014